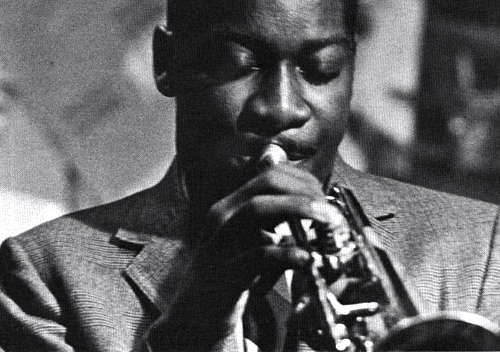

Booker Little, Jr. (trumpeter) was born on April 2, 1938 in Memphis, Tennessee and passed away on October 5, 1961 in New York City at the age of 23.

Little was born in Memphis, Tennessee to a trombonist father and piano playing mother. Both of his parents played in church groups, and his sister Vera later sang with the London Opera Company. At first, the boy attempted to learn trombone, then switched to clarinet at age twelve.

At fourteen, urged by his Manassas High School band director, Little switched to the trumpet for good. Memphis was a fertile musical city the boy grew up jamming with many future jazz notables, including pianist Phineas Newborn, Jr. and his guitar playing brother Calvin, trumpeter Louis Smith, who was also a cousin, pianist Harold Mabern, and saxophonists George Coleman, Charles Lloyd, and Frank Strozier.

In 1954, Little left Memphis to study trumpet and composition at the Chicago Conservatory of Music, where he earned a Bachelors of Music degree in trumpet. While in Chicago, he spent time jamming around the city with the likes of tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, as well as drummer Walter Perkins and bassist Bob Cranshaw, better known as the Modern Jazz Two (MJT).

While he was a sophomore at the Conservatory, Little roomed for nine months at the YMCA with saxophonist Sonny Rollins. Rollins exerted a strong influence on Little’s musical conception, encouraging the young trumpeter to form a distinct voice on his horn. “[Sonny] cautioned me about allowing myself to become overly influenced by other players,” Little told Nat Hentoff. “{He told me not to listen to too many records, because he felt I was listening to them mainly to emulate what the soloists were playing. “You’ve got to be you,” he told me, “whether that’s bad or good.}”

Rollins also introduced Little to drummer Max Roach in 1955, while Clifford Brown still held the trumpet chair in Roach’s group. Brown died the next year, and Roach approached Little to replace him in the group. Still in school at the time, however, Little declined and the seat was filled by Kenny Dorham. Upon graduating in June 1958, Little almost immediately flew to St. Louis to replace Dorham in Roach’s pianoless quartet – which also featured his old friend from Memphis, George Coleman.

Little remained in Roach’s group until February 1960, a remarkable nine month run during which he recorded prolifically with the drummer on albums such as On the Chicago Scene, Max Roach Plus Four at Newport, Deeds Not Words (which featured Little’s first recorded composition, “Larry-Larue”), Award Winning Drummer, and The Many Sides of Max Roach.

Booker Little 4 & Max Roach, the trumpeter’s first album as a leader, was recorded in New York in October 1958 with Coleman on tenor, pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Art Davis, and Roach on drums.

The purity of Little’s tone and his consistency throughout all registers is the most striking quality of his playing on these early recordings. His undeniable talent is audible from his first recorded note, with beautifully contoured, effervescent lines flowing joyously from his horn. The young trumpeter was still only twenty years old, however, and the influence of Clifford Brown is immediately apparent, making these early records an interesting study of a developing star striving to find his own voice.

After leaving Roach, Little settled in New York and began freelancing. In April 1959, he reunited with some Memphis schoolmates to record Down Home Reunion, a blues-heavy jam session. Altoist Frank Strozier and trumpeter Louis Smith joined Little in the frontline, backed by a rhythm section featuring the Newborn brothers, George Joyner on bass, and drummer Charles Crosby. Later in 1959, Little locked horns with fellow trumpeter Freddie Hubbard on Slide Hampton’s intricately-arranged Slide Hampton and His Horn of Plenty. He also recorded on Strozier’s The Fantastic Frank Strozier, which featured a strong solo by Little on Runnin‘ and vocalist Bill Henderson on Bill Henderson Sings. Both albums were recorded with Miles Davis’s rhythm section of Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Jimmy Cobb on drums.

1960 was a monumental year for Little. He rejoined Roach’s group in time to take part in the drummer’s groundbreaking album We Insist! – Freedom Now Suite, an intense statement of black historical consciousness and protest which teamed him with tenor saxophone patriarch Coleman Hawkins. Roach shines on his drum feature All Africa, on which Little plays in the ensemble.

That same year, Little also recorded his second album as a leader, simply titled Booker Little. It is a melancholic, subdued affair, which highlights Little’s burgeoning compositional skills. He took giant strides on this album, stepping out from Clifford Brown’s shadow.

1960 also saw the birth of one of jazz’s most important and tragically short frontline pairings: Little and multireedist Eric Dolphy. Despite its brevity, the partnership of Little and Dolphy still resonates today. Their first album from December 1960, Far Cry, is an undisputed classic and featured an all-star rhythm section of Jaki Byard, Ron Carter, and Roy Haynes.

Little’s association with the forward-thinking Dolphy audibly pushed him to new exploratory heights, and it is on this album that Little solidified his own distinct musical concept. By this stage in his young career, he sounded like no other: his dramatic use of dissonance, distinctive and atypical phrasing, and unique motivic development set him apart from other leading trumpeters of the era, such as Lee Morgan and Fredide Hubbard. Even as his improvisations became more and more challenging, his impeccable technique and meticulous control grew even stronger.

Dolphy and Little had established themselves as leaders of the “new thing.” Little shines throughout Far Cry, especially on Miss Ann, during which his eloquently executed lines are reminiscent of Clifford Brown, but colored with a dissonance that is all his own. The title track may be the best example of Little’s rapport with Dolphy; their independent melodic lines wrap around one another with a cunning playfulness, and their complimentary improvisations are simply outstanding. Little’s sudden, stunning leaps into the high register – a technique most certainly borrowed from Dolphy – are a shocking but rewarding interruption to the boppish flow of his line.

In 1961, Little described his harmonic concepts to Robert Levin in an interview for Metronome magazine: “I can’t think in terms of wrong notes – in fact, I don’t hear any notes as being wrong. It’s a matter of knowing how to integrate the notes and, if you must, how to resolve them. Because if you insist that this note or that note is wrong, I think you’re thinking conventionally, technically, and forgetting about emotion. And I don’t think that anyone would deny that more emotion can be reached or expressed outside of the conventional diatonic way of playing. . . . I’m interested in putting sounds against sounds and I’m interested in freedom also . . . which doesn’t limit the soloist. . . . In my own work I’m particularly interested in the possibilities of dissonance.”

That summer, Little and Dolphy were employed at the Five Spot Cafe in New York City with Mal Waldron on piano, Richard Davis on bass, and Ed Blackwell on drums. Dolphy and Little stretched out night after night, working out their daring ideas without the constraints of a recording studio. As in all cases where artists challenge the envelope of acceptance, some audience members and critics applauded their efforts, while others derided their boldness.

Fortunately for listeners, some of the Five Spot sessions were recorded, then released on three albums: Eric Dolphy at the Five Spot, Vols. 1 & 2, and Memorial Album. Tracks like Fire Waltz and Bee Vamp showcase both men confronting traditions and bravely clawing at the walls erected by their predecessors.

Other important recordings by Little in 1961 include his final two works as a leader, Out Front and Victory and Sorrow, which was rereleased as Booker Little and Friend. Both are stunningly beautiful albums. Also that year, he reunited with Roach to perform on his album Percussion Bitter Sweet, as well as in the brass section on John Coltrane’s Africa/Brass, and on Abbey Lincoln’s Straight Ahead.

Arguably considered to be Little’s masterpiece, the tempos on Out Front are slow and deliberate – even free at times – which allows Little’s gorgeous tone and melancholy to come to the forefront in his succinct improvisations and tempoless cadenzas. Little wrote magnificent, through-composed melodies with rich, sonorous harmonies for the frontline of himself, Dolphy, and trombonist Julien Priester. Victory and Sorrow was a more hard bop-oriented affair, but still challenging and with inspired blowing by all.

With his colossal talent just coming to fruition and a bright future lying ahead, Little succumbed to uremia on 5 October 1961 at the age of twenty three. But fortunately, in Little’s less than four years of recorded work, he left us with more to think about than many musicians do in a lifetime.